What we do (and don't) know about teacher shortages, and what can be done about them

For several months, NPR has been exploring the forces at work behind these local teacher shortages. Interviews with more than 70 experts and educators across the country, including teachers both aspiring and retiring, offer several explanations: For nearly a decade, fewer people have been going to school to become teachers; pay remains low in many places; and, with unemployment also low, some could-be teachers have chosen more lucrative work elsewhere. Researchers and educators also point to a cultural undertow pulling at the profession: a long decline in Americans' esteem for teaching.

Educators shared stories of students learning Spanish from computers, and superintendents doing double duty as substitute teachers. But they also shared stories of creative, committed efforts – from San Antonio to Hooper Bay, Alaska – to grow a new generation of teachers, while doing more to make sure veteran teachers want to stay.

It’s hard to know the size of the problem

"Teacher shortages are poorly understood." That's according to a paper published last summer. The reason they're poorly understood? A profound "lack of data" at the federal- and state-level.

It's important to think of school staffing challenges not as one, national shortage, but as innumerable, hyper-local shortages. Because nationally, "we have more teachers on a numeric basis than we did before the pandemic, and we have fewer students" due to enrollment drops, says Chad Aldeman, a researcher who studies teacher shortages.

"Contrary to popular talking points, there is no generic shortage of teachers," reads one deep-dive into the available data. "The biggest issue districts face in staffing schools with qualified teachers is... a chronic and perpetual misalignment of teacher supply and demand."

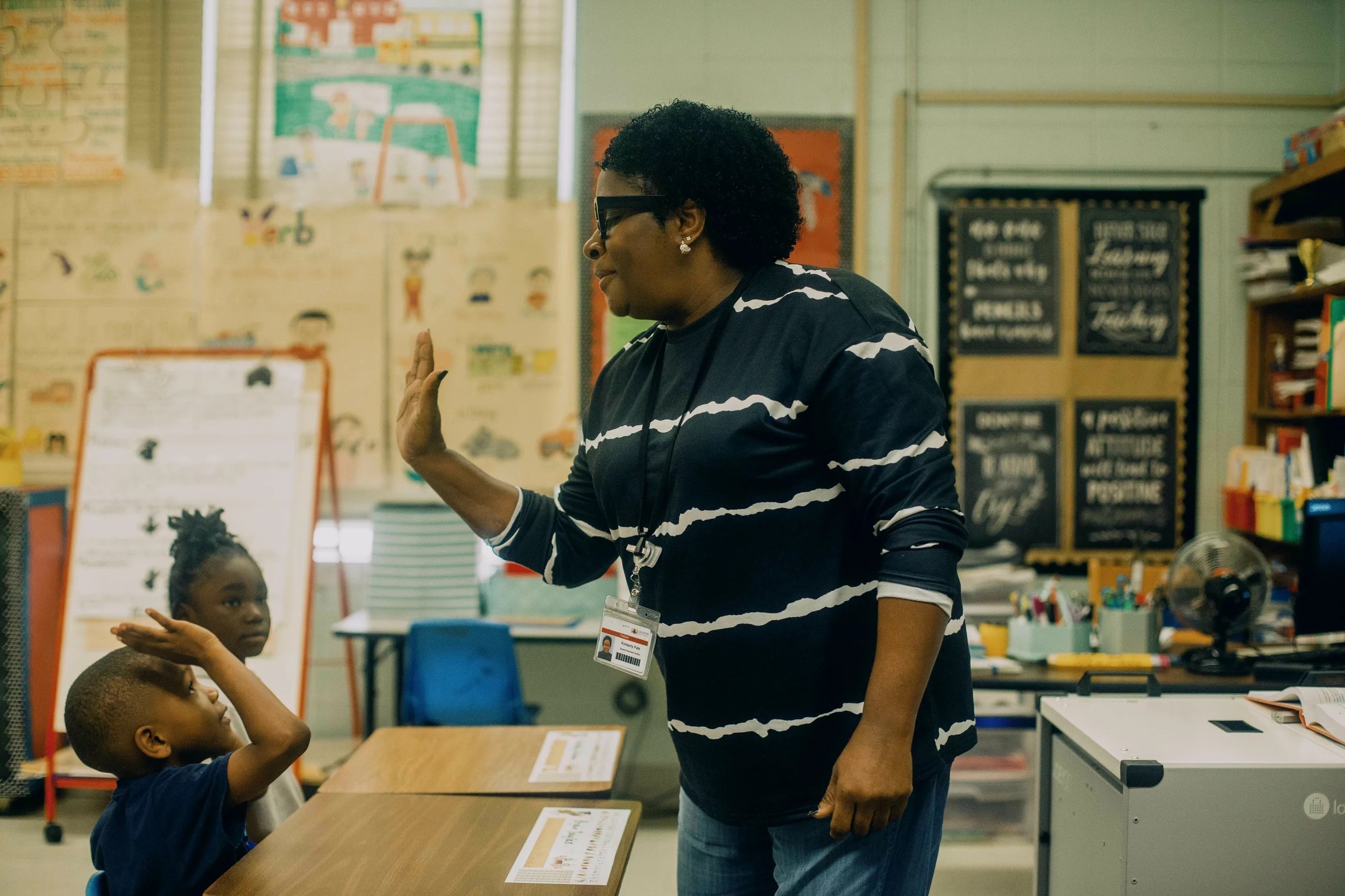

There's an inequity around teacher shortages

Many districts "have dozens of teachers applying for the same positions," Tuan Nguyen explains. "But in a nearby district that is more economically-disadvantaged or has a higher proportion of minority students, they have difficulty attracting teachers."

It turns out, shortages are a lot like school districts themselves. They often begin and end at arbitrary lines that have more to do with privilege and zip code than the needs of children.

-Short excerpt from the aricle, review for more or to listen in on NPR.